Carter Brey, the Principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic performed the Bach solo cello suites in New York a few years ago. He played on two of my cellos set up in Baroque disposition. For the Sixth suite he used a five-string cello I made specially for the occasion. In order to get a clear idea of what he was looking for in sound and response, I asked him to talk about the suites and his interpretation.

In these videos he reviews the history of the score of the Suites, and the evolution of his concept from the traditional Romantic performance to one that incorporates historically informed performance practices. He includes demonstrations of specific passages using the cello in Baroque disposition, with a matching bow; and using a modern and Baroque cello (both of which I made), he shows the difference in interpretation that each setup allows.

How the Project Came to Be:

The article from Strings Magazine

One day late last June I got a call from Carter Brey, the Principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic. He had been asked to perform the Bach Suites for solo cello as a part of a week-long festival of the composer’s work the orchestra would be doing the following March. The concert would take place at the Holy Trinity Church, just down the street from Lincoln Center, on Central Park West. Elegantly soaring yet intimate, with excellent acoustics, the church nave is the perfect setting for the Suites -- even more so because Carter’s concept of the music had evolved considerably over the years, and he wanted to ground his interpretation in Baroque performance practices.

And so the purpose of the call was to ask if I could convert the setup on the cello I had made for him from contemporary to Baroque. It could easily be done, I replied: a different bridge, tailpiece, and an endbutton instead of a pin. Maybe a soundpost, I wasn’t sure. Easy enough, that is, but not by me; I had no experience in that field. Monical’s your man – and lucky you, he’s a short ferry ride right across the harbor.

William Monical is, in a word, the dean of Baroque instruments. Trained as a violinmaker in Mittenwald and London in the early years of the baroque revival, Bill left his seat at the repair bench at Jacques Francais in the late Seventies to concentrate on the growing interest in original performance practice. But his 1989 exhibit at the Library at Lincoln Center, Shapes of the Baroque, wrought an epochal change in the way all violinmakers thought, not just those interested in early music: not only demonstrating how fluid and diverse instrument making had been, Bill made a clear and convincing case that string technology was what had driven the evolution of design. He made us see that what we were building was not a cello with strings attached; it was an amplifier, whose sole purpose was to make the vibrating string audible. Start with the string, and work outward from there. A few years ago, realizing I couldn’t even remember the last time I had cracked open any but a few of the hundred or so violin books in the library I had built up over the years, I sold them. I kept fewer than half a dozen that I considered indispensable – and the catalog for his show was one of them.

Pleased to have an excuse to pay a visit to Bill, who had been such a generous mentor to me when I had been in New York (as he has been to so many of my colleagues over the decades), I met Carter late on a gorgeous summer morning at the ferry terminal. He had both his cellos with him: the Milan period Guadagnini and the one I had made. Guadagnini cellos are quite rare, and diminutive – in both body size and string length. The latter being the crucial dimension in being able to go back and forth between the two without having to adjust, I had copied his to the millimeter. I’d like to say that we spent the voyage across the harbor discussing the Suites, the demands of the venue, or even catching up on the latest news in the world of music; but the wind was fifteen knots out of the southwest, so we talked sailing and watched with envy the one or two sloops tacking out of the way of the big boat as it chugged steadily past the Statue of Liberty.

Musical matters moved to the fore as soon as we had climbed the steps and entered the large, high-ceilinged first floor office of Bill’s house, with its magnificent view of the New York skyline across the harbor. “Let’s see the cellos!” Bill said after a quick hello. The depth of his knowledge and expertise is exceeded only by his enthusiasm, and his pleasure at seeing the two instruments was evident. While generally acknowledged as the pre-eminent expert in the world of early music, Bill is equally sought out for his skill with the more ‘traditional’ classical instruments. He has few equals in setup and adjusting -- the fine art of realizing the full potential of an instrument’s sound, and personalizing it to the needs of the musician playing it. And as someone who has always seen the world of violins as an ongoing continuum, he has from the first been an avid proponent of contemporary making.

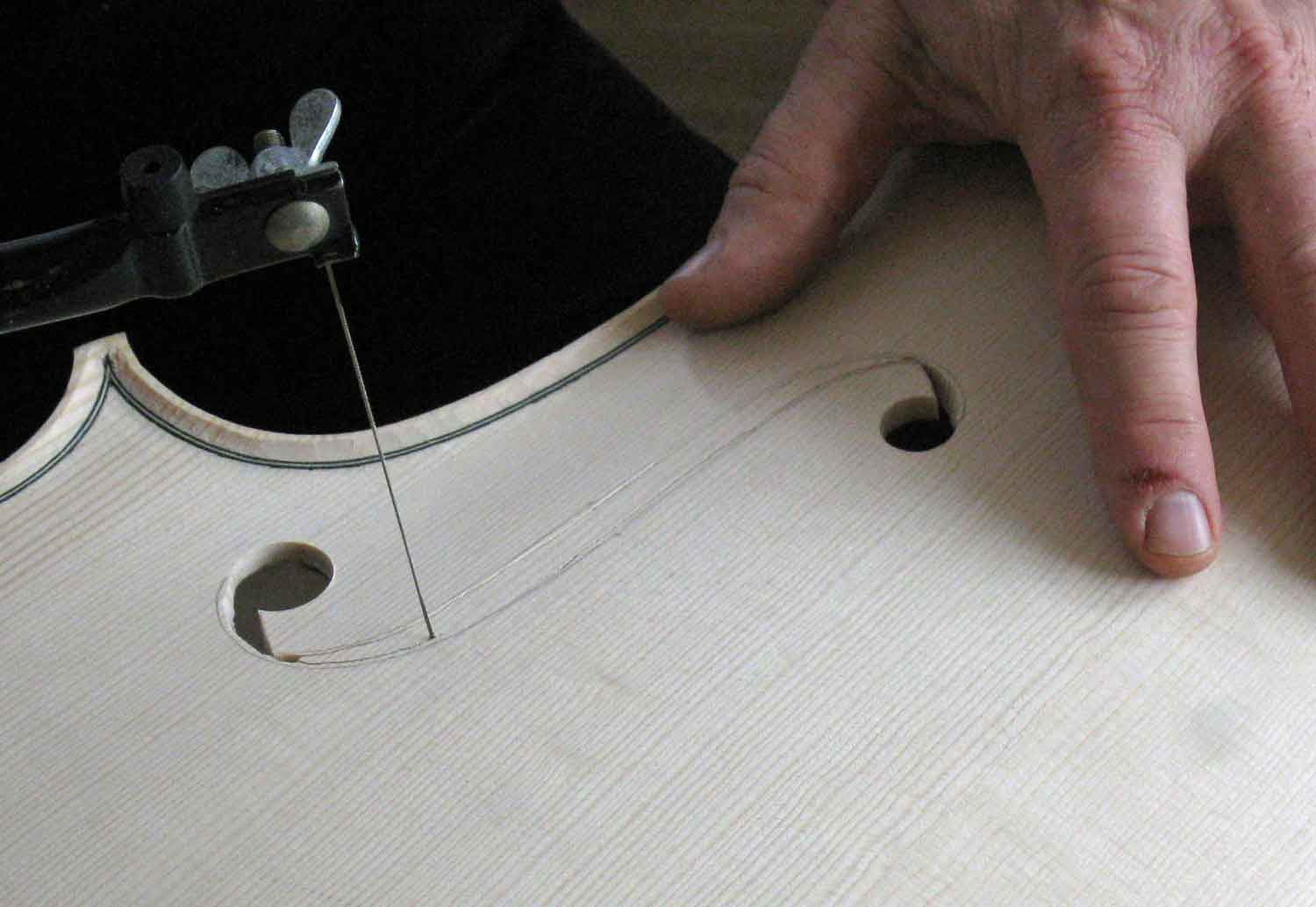

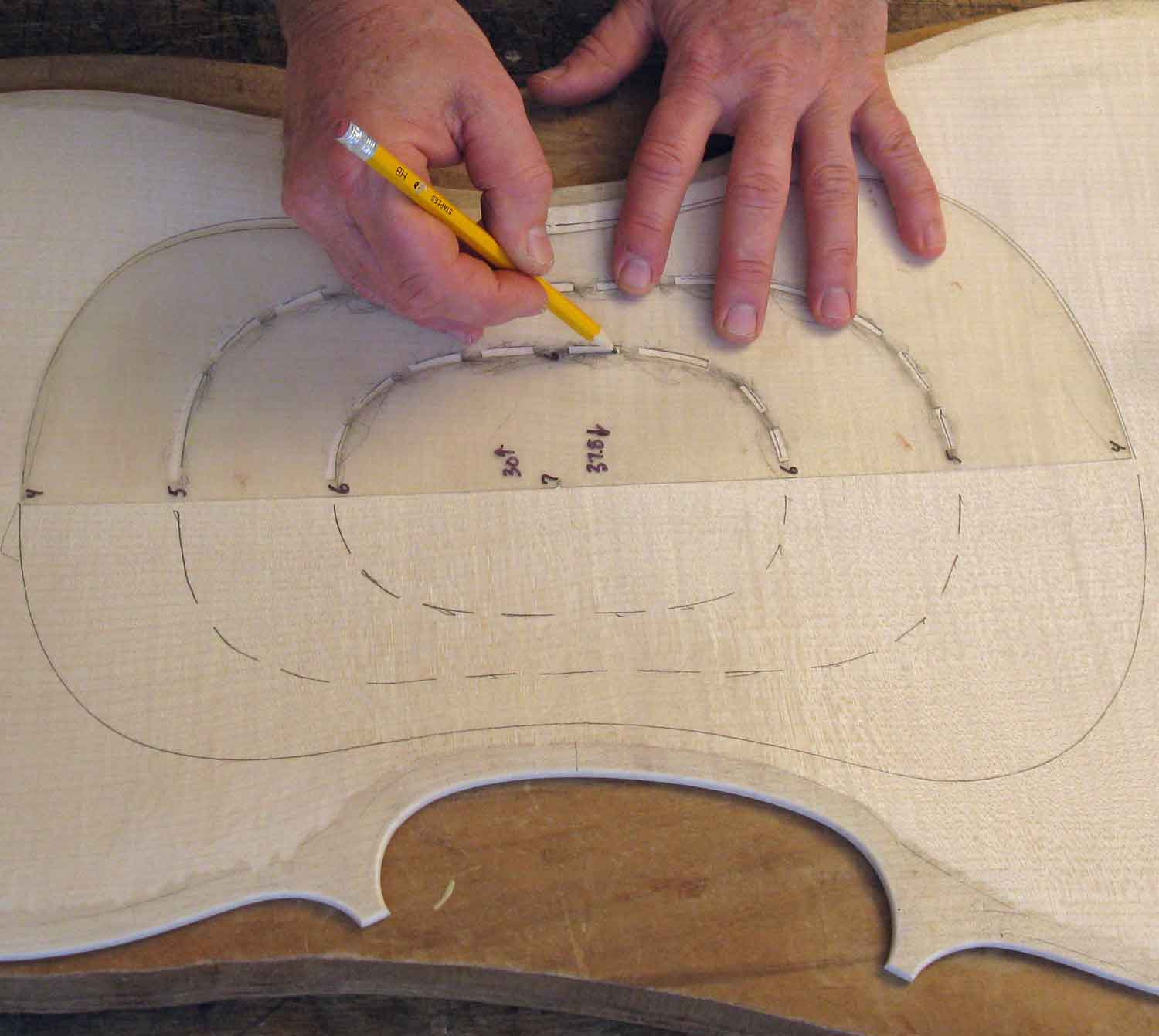

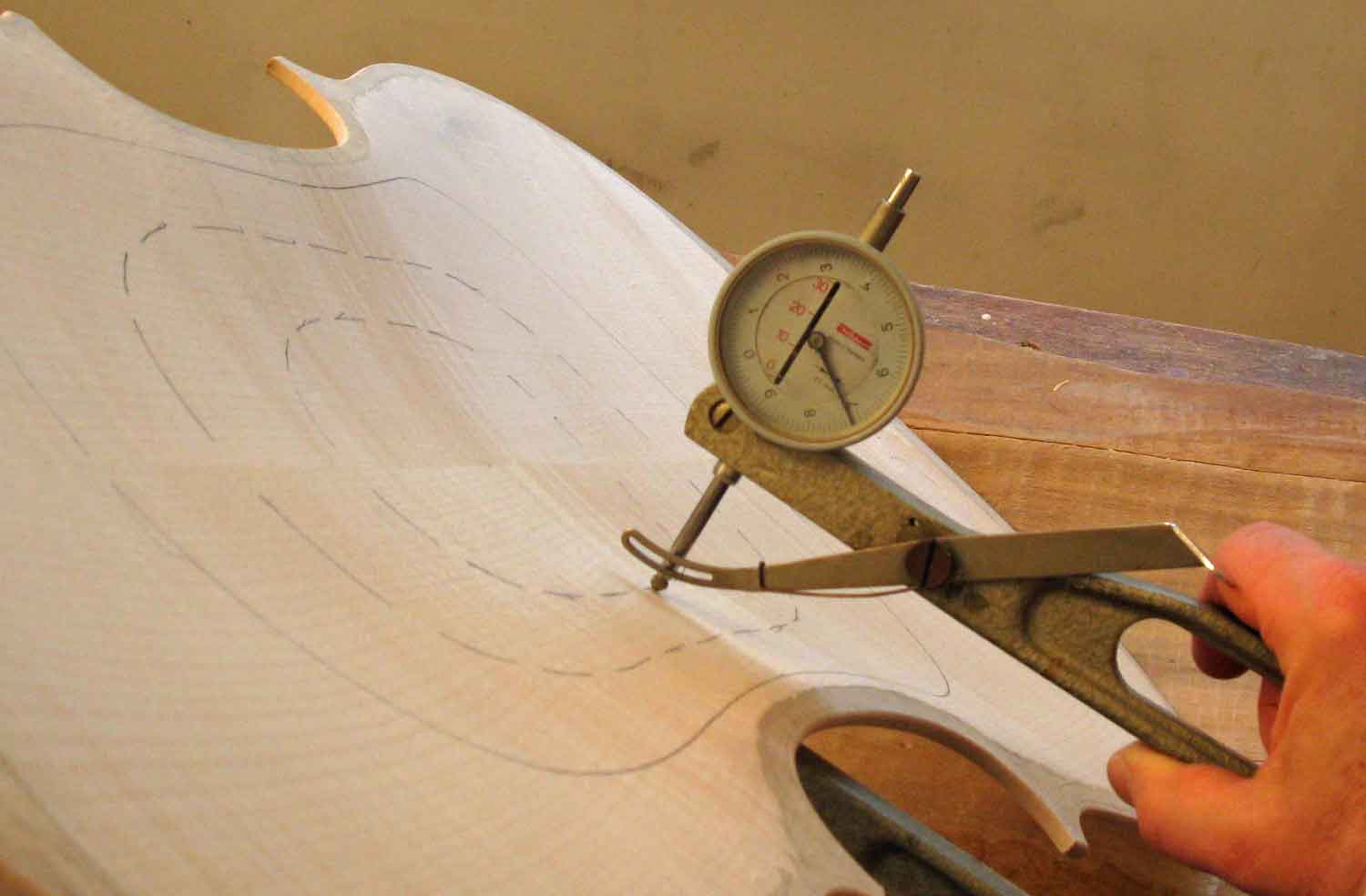

A quick glance was enough for him to decide that the Guadagnini was not the proper instrument of the two for a Baroque setup; the model, arching and f-hole placement were not right for the lesser tension of gut strings. While I had duplicated the string length, both overall and in the division between neck and body, I had used my own pattern in making the cello. The waist and spacing between the f-holes was wider, and the arch more gradual and springy; it would respond better to the different setup. Taking down meticulous notes, Bill listened and watched as Carter played. While still using the contemporary setup, he had already begun practicing the suites with a Baroque bow.

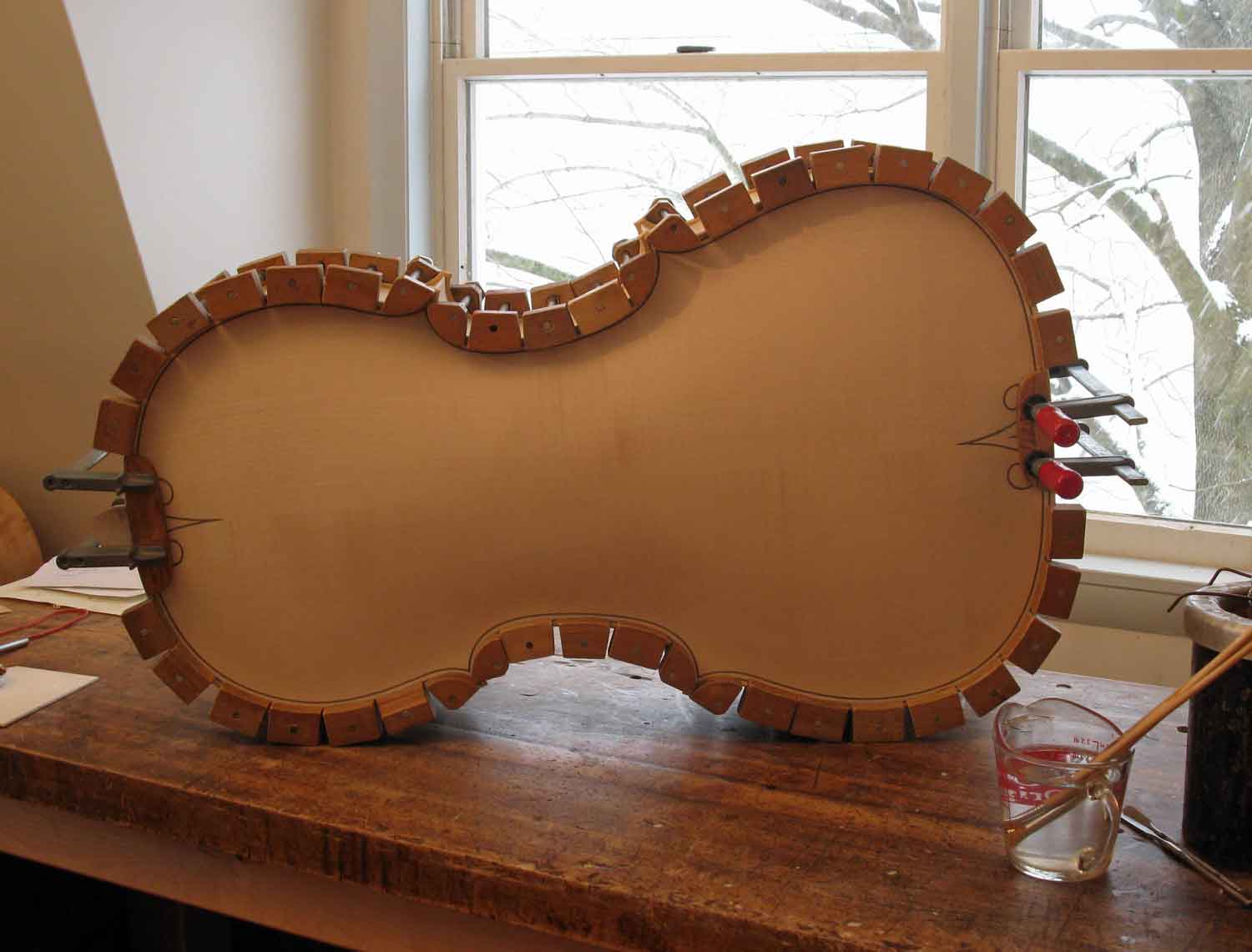

The matter of the Baroque setup settled, Carter handed the instrument to Bill for the necessary work. “And what about the 5-string?” he asked. He had mentioned to me that he wanted to play the Sixth Suite as originally written – on a 5-string cello. That was not going to be so easy; I’d never even seen one. Not even in a museum collection. Bill could find one for him to try it and see how it felt to play the Suite on 5 strings, but finding one for the full length of time necessary to prepare for the concert? That would be a different matter. And there was no question that Carter would need some time -- adding a new string disrupts a lifetime of ingrained shifts and bow crossings. It would be like relearning to ride a bicycle, but with your hands crossed.

But Bill had a solution. His enthusiasm was contagious, buoying our step as we walked down the steep stairway to the sidewalk. It was only halfway down that I paused and said to Carter, “Am I mistaken, or did I just agree to make a 5-string cello?”

“Yes, I think you did,” Carter replied, and we both laughed. Indeed I had. When the subject of finding one for the concert had come up, without missing a beat Bill had said, “Jim, you could just make him one.” And without missing a beat, without even thinking, I had nodded; of course I could make him one.

“It’s going to be fun,” I said. And it would be. In some ways it was an odd project; the literature for the 5-string cello begins and ends with one single piece of music: the Sixth Suite. I had just agreed to spend a month making a cello for thirty-two minutes of music. But so what? It was thirty-two minutes of the most glorious music ever composed – and this was a chance to hear it as it as Bach wrote it.

When I had first arrived in New York from violinmaking school, in the late Seventies, I had been taken in as an apprentice by Vahakn Nigogosian, one of the most revered restorers and experts in the world. At that point he was could easily have left the business for a very comfortable retirement; he had learned violinmaking in Paris in the Twenties, returned to his native Istanbul (or Stamboul, as he called it) where he had run his own shop for decades – and then in the Fifties pulled up stakes and moved to New York, family in tow, when the opportunity arose to work with Sacconi at Wurlitzer. But violins were in his blood; he could no more retire than a hawk decide to give up flying. Carter, a young grad student with Aldo Parisot at Yale, used to bring his cello into the shop.

Aside from the training, Nigo gave me the best advice I’ve ever gotten: watching me work, he would shake his head and say “Jeem, slow down. Vy you work so fast? Should be you enjoy yourself.” I never slowed down – I like to work fast – but I’ve enjoyed every moment of every violin I’ve ever made. Even making the fingerboards, which is about as dirty a job as you can find in the workshop. Making fiddles offers a triple reward; you can completely lose yourself in making them; then, once it’s done, you string it up, and hear a voice come alive, new to the world; and finally, when it finds the right hands, it makes it possible for them to sing.

I had another cello to make so it was well after Labor Day before I could begin work on the 5-string. As I was making it, Carter was refining his approach and style, and working with Bill on different strings and adjustments. But I was growing increasingly skeptical that the cello was going to work – the response was too slow, the sound lacking that focus and resonance when it’s properly centered. It confirmed my initial reservations about the cello: that the gut strings were just too short to maintain proper tension.

The turning point was when Carter decided to drop the pitch to 415; this reduced the tension even further. The strings were perilously close to the point where even the pitch itself becomes uncertain – it will waver as the bow hits and then pulls the string. As much as he would never say it, it was clear to me that the cello was just not working the way he wanted it to.

More than the fundamental problem of the string length, though, the style of the cello was wrong. It worked better for the Baroque setup than the Guad, and Bill had done an admirable job of adapting it with his setup and adjusting, but the truth was that it wasn’t what it was designed for. It was built for a soloist playing the modern literature: sostenuto, with full pressure for the full length of the bow. The Baroque style of bowing is completely different. Carter calls it gestural. It’s almost like plucking, in a way; a firm attack, but then the bow pulls away, letting the string ring (he demonstrates this in an interview on the Strings website). A cello designed for that can be adapted for a more contemporary style, but there’s a limit to how far a cello designed for the Romantic literature can be retrofitted. You can kind of get there, but it will never be exactly right.

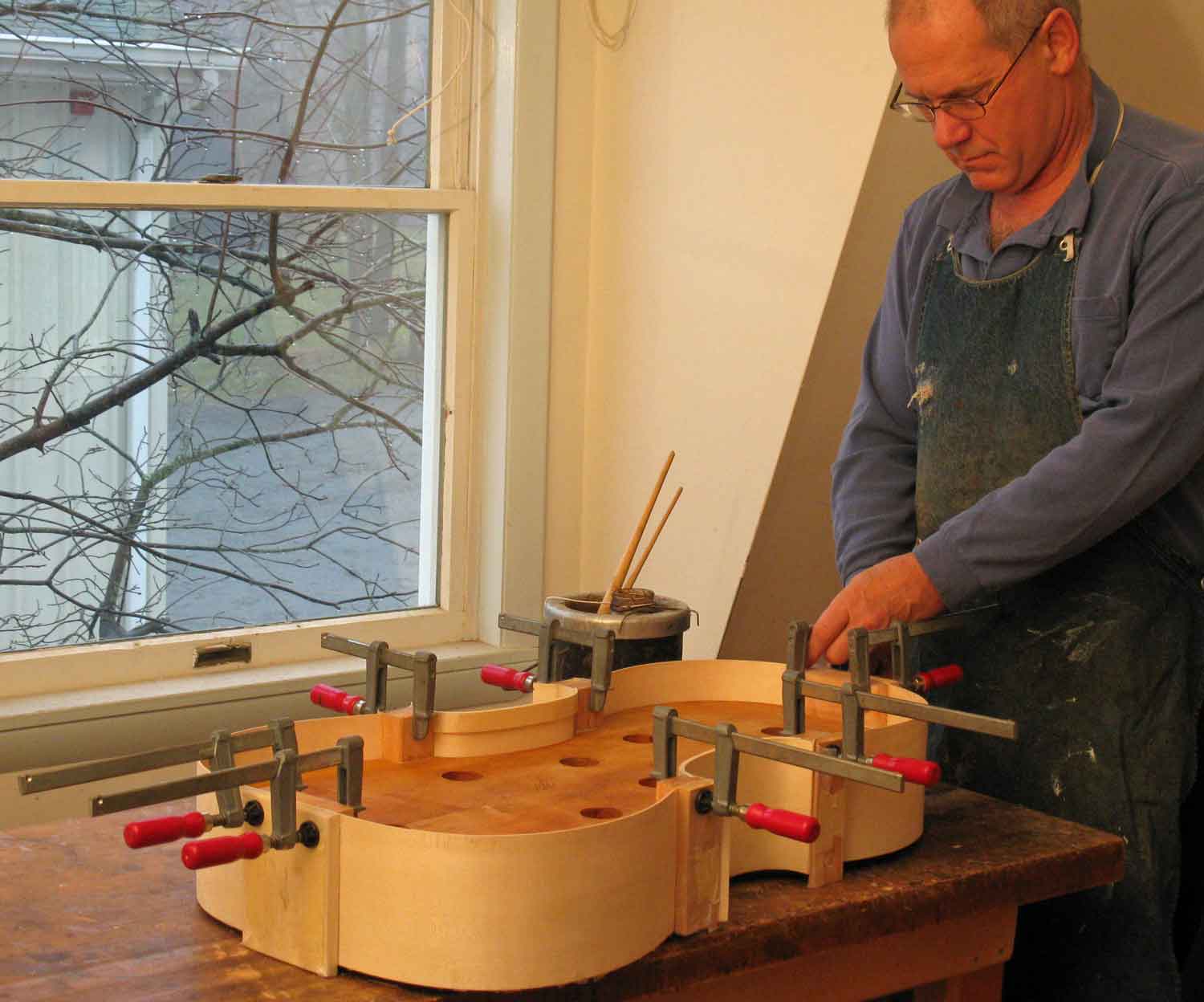

But now there was a looming problem, a much more urgent and serious one: time was running out. Here it was after Thanksgiving, and the concert was now not way off in the dim future, but only months away. And now we needed two cellos – a Baroque one with a proper string length, and a 5-string to match, so that Carter could make a seamless transition from one to the other during the concert. Thank god I had ignored the first part of Nigo’s advice – there was still time to make a 5-string cello. But two cellos?

Luckily, I remembered that there was a cello of mine not being used that might suit Carter perfectly -- and even better, that the owner would very likely be willing to let him use it for the long period of time leading up to the concert. I knew that because the owner happened to be my older son. I had made the cello for him when he started playing with the local county orchestra when he was in high school. But in college he had taken a detour into rock and EDM, so the cello, as far as I knew, was resting in its case at home.

When I broached the subject my son was thrilled at the idea of Carter using it. The string length of the new cello was two centimeters longer – just enough to give the strings the tension they needed. More than that, though, the model was better. I had designed it knowing that my son would very likely end up using it in primarily a chamber setting; while he enjoyed playing, he was not on a conservatory track. I wanted it be more easily accessible, in sound and response. The model was rounder, with a fuller arch and a deeper channel, the f-holes cut to make the top more flexible, the ribs shallower for an easy and quick response – it would work perfectly with a Baroque setup.

As it turned out, I had to make a quick trip out of town for a week, so I dropped the cello by Carter’s on my way. “Just give it a try,” I said, handing it off. “We’ll talk when I get back.”

“I’m convinced,” he said immediately when I called upon my return. “This is exactly what I had in mind. It rings.”

Bill’s proper setup for the new cello only convinced us both that we had now found the right cello. I quickly set a modern neck into what was to have been the 5-string cello and started the new one. But then I ran into a new problem. The room I use for varnishing doubles as a spare bedroom when needed -- and we would be filled to capacity with family during the holidays, just when the new cello would be ready for the undercoat. There was no way around it; I wouldn’t be able to start the varnishing until New Year’s Day.

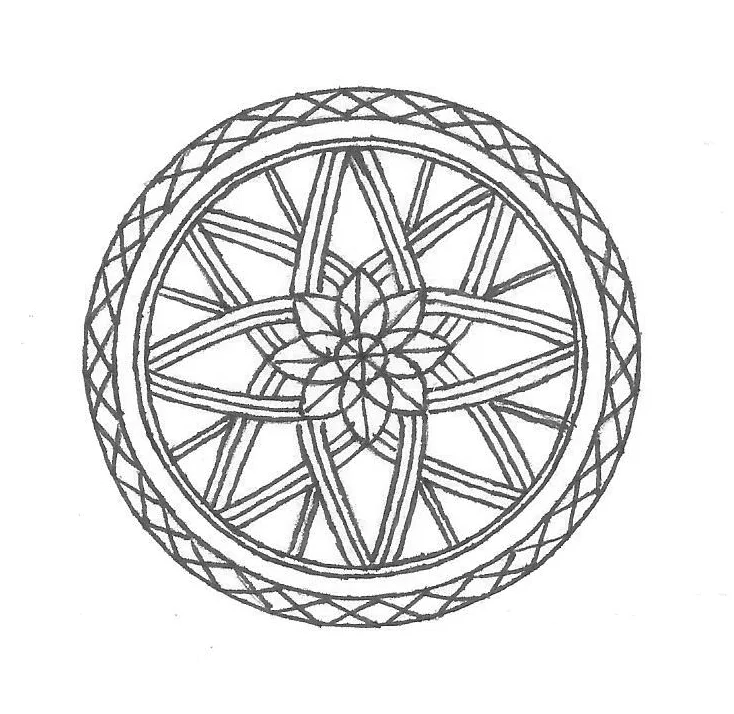

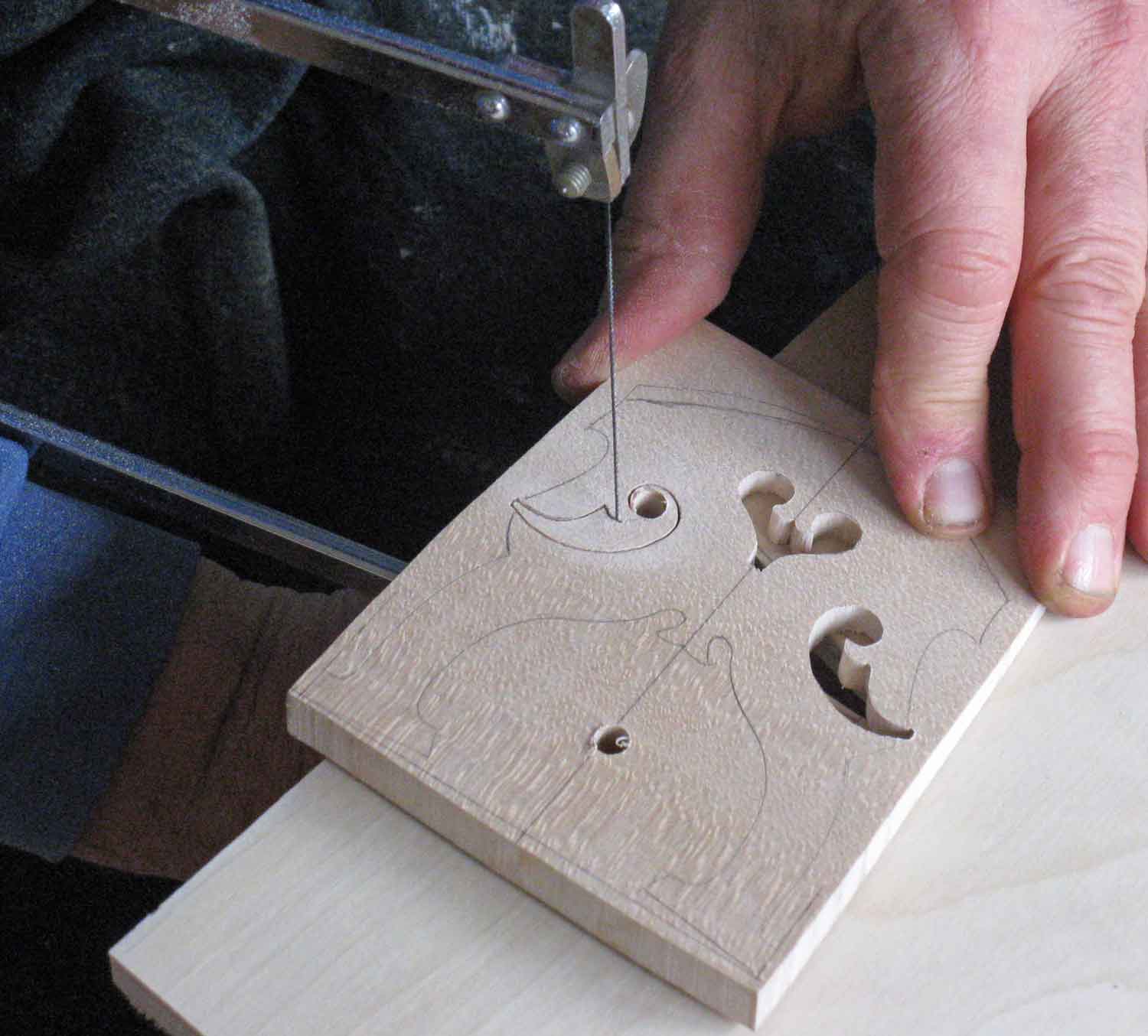

But that turned out to be pure serendipity. It gave me three extra weeks. I decided that I would do something I had always wanted to do – a rosette in the top. And, just to balance it out, double purfling. And – why not? – some decorations on the back. As it turned out, I got it strung up in early January – just as Carter was getting back from a tour. He wouldn’t have been able to use it earlier anyway.

I went down to his apartment a few weeks after I delivered it to hear the cello with Bill’s setup and adjustment. Carter played some of the first five suites on the regular Baroque cello. He then switched to the 5-string and launched into the stirring opening passage of the Sixth. When he reached the part that gives cellists nightmares – the endless shift up the fingerboard – he instead just used the new top string. It was completely different from anything I had heard before. It sounded so natural; it danced. It was as though the missing channel on a stereo had finally been hooked up and I could finally hear the music in its entirety.

Making the cello had turned out to be as much fun as I had ever had – designing it, making the composite fingerboard, shaping the wider neck; most especially, cutting the rosette. But hearing the Sixth Suite as it was meant to be – that was a gift. Making instruments in some ways is just a matter of making things right; and this was the way it was supposed to be.